THE ANATOMY OF MEZCAL

THE PLATFORM

Anatomy of Mezcal focuses on four themes: Agave, Terroir, Process and Mezcal. Each section is designed to provide you relevant information on each topic despite they are all interconnected.

This platform is bilingual and our collaborations can be in Spanish and English.

This material is an adaptation of the original book The Anatomy of Mezcal, 2013, ISBN: 978-0-9754632-0-8, an educational initiative led by Dr. Iván Saldaña Oyarzábal, agave plant, agave distillates and spirits specialist.

If you are interested in collaborate please email us at megusta@anatomiadelmezcal.net

In order to start building our community please join our Facebook Page: Anatomía del Mezcal

© 2013 Iván Saldaña Oyarzábal

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, or recorded in or transmitted by an information retrieval system, in any form or by any means, mechanical, photochemical, electronic, magnetic, electro-optical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

ARTÍCULOS RELACIONADOS:

MEZCAL DIVERSITY

To understand mezcal, we need to define and identify mezcal as one thing, but at the same time as a result of many parts.

Mezcal is one and has an identity built of all its expressions. On one hand, is a distilled alcoholic beverage with an ancient cultural heredity, produced from the fermentation of agaves and aloes species endemic to Mexico. On the other, mezcal is expressed in various forms, tastes, cultural heritages, and biological technology, offering the most diverse heritage alcoholic expressions produced by man today.

We try to understand mezcal by dissecting the ingredients that make it different. Each one is, in itself, a way to get to it.

It is within our capacity to keep alive the rich heritage of mezcal through the many biological and cultural expressions in which this drink is based.

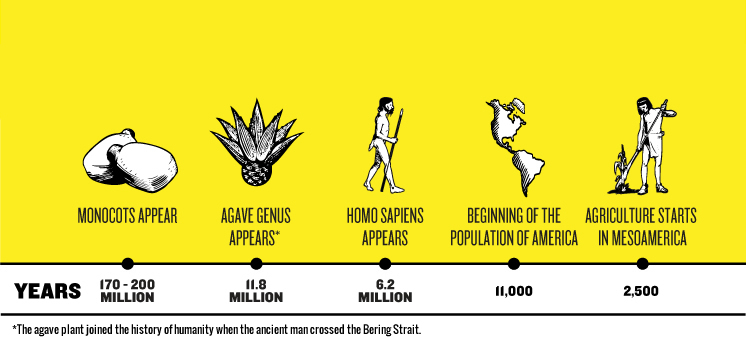

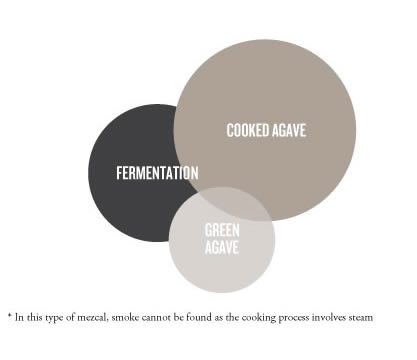

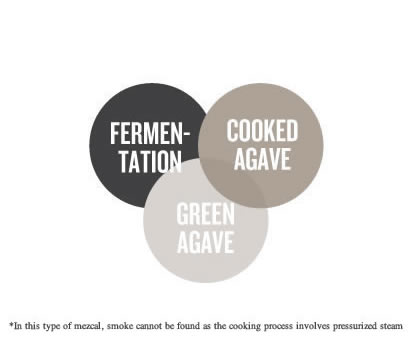

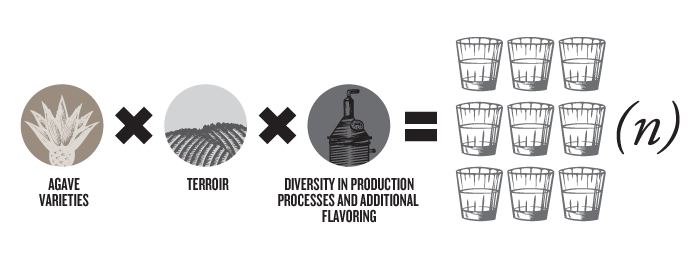

The diversity of mezcal comes from the combination of many different factors that confer a broad range of tastes and aromas. It can be said that there are three main sources of diversity in mezcal or agave distillates that should be considered to create classification axes:

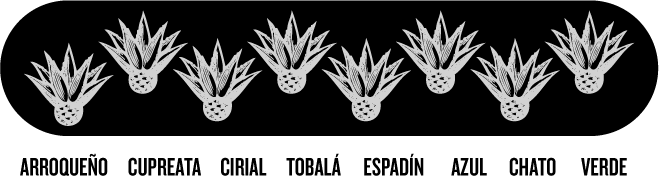

A.THE RAW MATERIAL: AGAVE VARIETIES

Refers to the species of agave used —either a single type or a combination, whether wild, cultivated or semi-cultivated— and how the plantations are managed, be they certified organic or using herbicides, pesticides and chemical fertilizers. These factors greatly determine the outcome of the mezcal.

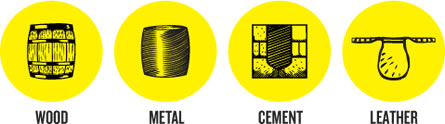

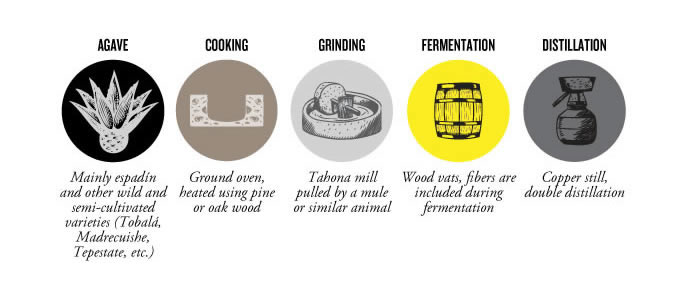

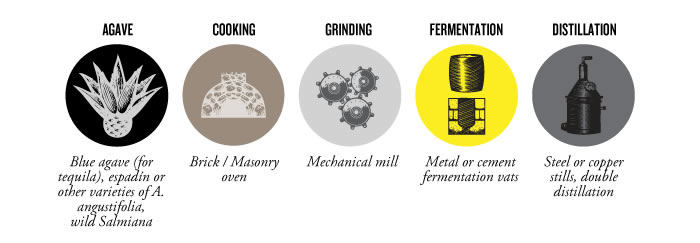

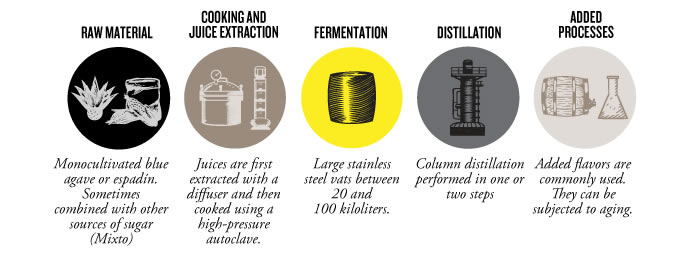

B. DIVERSITY IN PRODUCTION PROCESSES AND ADDITIONAL FLAVORING

Refers to the methods used throughout the process, such as: jima, cooking, milling, fermentation and distillation. Additional processes include aging in wood, using fruits and herbs for flavoring effects and adding insects or larvae. Cultural heritage and family traditions define which technologies and recipes are used by the maestros mezcaleros (master mezcal distillers) in their palenques (rustic distilleries) and greatly influence the taste of the drink.

C. TERROIR

The concept of “terroir” includes the sum of the geological, climatic and environmental factors that give character to a mezcal. Cultural characteristics may also be considered part of the terroir. Differences in terroir contribute substantially to the wealth of variety in mezcal.

Even after following the same production process and using the same species of agave, the area in which the plant grows can greatly affect the final taste of a product. An agave can express certain aromatic compounds more dominantly than others depending on the land where it grows. Moreover, humidity and temperature affect populations of yeasts and microorganisms active in the fermentation processes.

There is still very little technical or scientific information to explain the effects of the specific terroirs on mezcal. It is important to understand that the use of the term “terroir” (or terruño) refers to many factors, including the climate on the hillside where the agave grows, the location of the palenque (where fermentation and distillation occurs) and the decisions made by the maestro mezcalero.

To preserve its richness, we must avoid promoting only a few production methods based on efficiency, or the use of only select varieties or species of agave. We must not promote artificial regional restrictions on the production of this drink. This may be a significant challenge but in order to preserve many expressions of this patrimony, we must ensure that the only regulations in the production and sale of mezcal and other agave distillates are based on quality and sustainability, not political or economic factors.

ARTÍCULOS RELACIONADOS:

WHAT IS MEZCAL?

Mezcal, in its oldest and most accurate definition, is a spirit distilled from the fermentation of sugars derived exclusively from any species or variety of agave plants.

Agaves are succulent, rosette-shaped, spiky plants commonly known as “maguey” which are distributed throughout the Mexican territory.

History and politics have alienated the technical and legal definitions of mezcal from its original definition. The commercial use of the word “mezcal” has been artificially limited to products coming only from specific regions in Mexico, preventing producers outside the designated area from legally calling their product Mezcal.

Currently, agave-derived beverages of various qualities are available. Unfortunately, most of the liters of agave distillates sold in Mexico are not 100% agave, but are combined with other sugars from cane or corn, affecting product quality. Additionally, there is a huge ethical problem among certain novice and established producers who adulterate their spirits to lower costs and increase volumes.

GLOSSARY

Anatomy:

Science, which aims to describe the number, structure and relationships of the different parts of something. Dissection or separation of the parts of a whole.

Terroir

Refers to the particular features or characteristics developed in plants or products —such as mezcal— as a result of geography, geology and climate of where they are grown or produced. This concept is central for the creation of appellations of origin and geographical indicators.

Terpens:

It is the most abundant group of essential oils in plants. Terpens have a wide variety of functions, one of the most important is to serve as a repellent to insects, bacteria, fungi and herbivores. They are responsible for specific aromas and flavors, and are widely used in the food industry when isolated for perfumes and food additives.

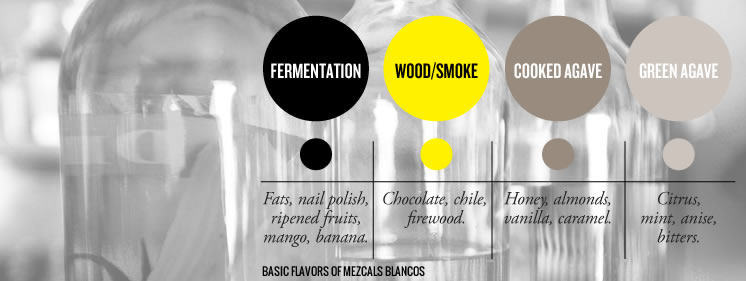

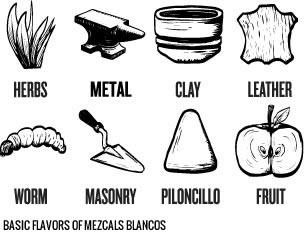

Esters:

Esters are formed when fatty acids come in contact with alcohol. In agaves, esters are used for building the waxy layer of leaves, which reduces water loss by insulating the plant tissues and preventing water evaporation. Esters provide important organoleptic characteristics to spirits, giving notes of ripe fruits and flowers. During fermentation, esters can build. In mezcal, long periods of fermentation lead to the intensification of notes like banana, mango and berries.

Fermentation Congeners:

Compounds typically formed or modified during the fermentation processes. Congeners usually have a volatile nature and get into the final product after distillation. These compounds are of different chemical nature with higher alcohols, esters, ketones, acetyls and aldehydes. Their organoleptic properties give flavor to spirits and can be manipulated by changing the distillation patterns.

Scientific Name:

Biologists and naturalists often use single-reference naming devices for each type of organism. They are typically adaptations of Latin root words, naturalists’ last names or places where the organisms come from. The first word refers to the “genus”, or the biological group they belong to, and the second refers to the precise species. A specie may or may not posses subspecies and varieties within itself. The surname of the scientist who named it is commonly placed in parentheses after the scientific name.

ARTÍCULOS RELACIONADOS:

IVÁN SALDAÑA OYARZÁBAL

Agave plant and agave distillates specialist.

PhD in biochemistry from the University of Sussex, England. Iván Saldaña Oyarzábal was born in Guadalajara, México and grew up with agave as part of his family’s business. From a young age, Dr. Saldaña worked on environmental and social projects in rural communities of central and southern Mexico, as well as in conservation areas in the United States and Chile. His thirst to understand more about nature led him to study biology and pursue graduate studies in various countries, and his academic research has focused on understanding the evolutionary path of the agave plant, the biological mechanisms that have shaped the agaves diversity and the biochemical characteristics that have allowed their adaptation to arid climates. Dr. Saldaña has worked with various companies as a specialist in scientific and technical matters of agave, as well as issues related to quality assurance in production, product innovation and environmental responsibility. In 2011, Dr. Saldaña founded Montelobos Mezcal (www.montelobos.com) and dedicated himself to developing and producing an organic, artisanal, Oaxacan mezcal. He maintains an advisory role in the spirits industry and remains devoted to agave and mezcal education, presenting at industry conferences and events and overseeing the current platform.